Reinforcement Versus Punishment in Dog Training.

The debate between punishment-based and reinforcement-based dog training has existed for decades. Historically, punitive methods were widely accepted across many areas of dog training, from police and working dogs to family pets. Older generations were often advised to shout at dogs, physically correct them, or rub their nose in urine or faeces following indoor accidents. These approaches were rooted in outdated beliefs about canine learning and behaviour.

Over recent years, scientific research has significantly advanced our understanding of how dogs learn and, just as importantly, what compromises their welfare. One influential but outdated belief was Dominance Theory, sometimes referred to as Alpha Theory, which suggested dogs must be dominated and that owners should function as “pack leaders.” This theory has since been scientifically disproven and was based on flawed interpretations of captive wolf behaviour rather than natural canine social systems. Its legacy persists in outdated advice, such as recommending physical domination in response to growling, despite evidence that such approaches increase fear and aggression risk and are both harmful and unnecessary.

Modern behavioural science instead highlights the ladder of aggression, which describes how dogs communicate discomfort through a series of escalating signals, such as turning away, growling, snapping, and biting. A growl is not defiance, it is communication. When dogs are punished for early warning signals, those signals may be suppressed rather than resolved. As a result, the next time the dog feels threatened or uncomfortable, they may escalate directly to biting without warning. This outcome is not the dog’s fault, but a consequence of removing their ability to communicate safely.

Dogs are sentient beings, not machines. Expecting perfect obedience at all times fails to account for emotional state, learning history, environment, and stress - all of which play a role in behaviour.

How Dogs Learn: Operant and Classical Conditioning

Most dog training relies on operant conditioning, where behaviour is shaped by its consequences. Behaviours that lead to desirable outcomes are more likely to be repeated, while behaviours that result in unpleasant outcomes may decrease in frequency.

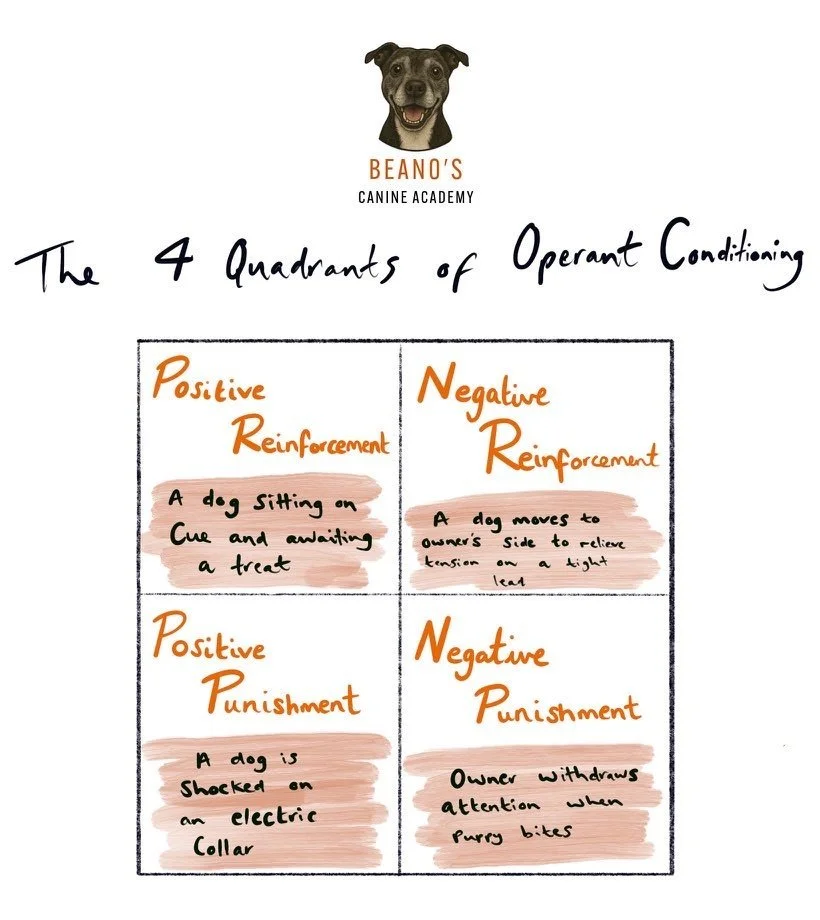

Operant conditioning consists of four quadrants:

Positive reinforcement: adding something desirable (e.g. food, toys, praise) to increase a behaviour.

Negative punishment: removing access to something desirable to reduce a behaviour.

Positive punishment: adding something unpleasant to reduce a behaviour.

Negative reinforcement: removing something unpleasant when the dog complies to increase a behaviour.

Negative reinforcement is commonly misunderstood. It involves the removal of pressure or discomfort when the dog complies, such as releasing lead tension once the desired behaviour occurs. Typically, positive punishment and negative reinforcement work hand-in-hand. And vice-versa, positive reinforcement and negative punishment are used together.

Dogs also learn through classical conditioning, where an emotional or physiological response becomes associated with a previously neutral stimulus. Pavlov’s dogs famously learned to salivate at the sound of a bell once it had been repeatedly paired with food. In everyday training, classical conditioning explains how dogs form emotional associations with people, environments, cues, and training equipment.

Reward-Based Training and Canine Welfare

Reward-based training focuses on reinforcing desired behaviours using food, toys, praise, or play, while also teaching alternative behaviours and managing the environment to reduce opportunities for failure. This approach sets dogs up to succeed rather than correcting them for mistakes.

Across species, reward-based training is widely used, from dolphins and horses to zoo animals and companion dogs, demonstrating its effectiveness beyond a single species. Importantly, reward-based methods prioritise welfare.

Research consistently links reward-based training with positive welfare outcomes. Dogs trained primarily with rewards show lower levels of fear, aggression, and stress-related behaviours and demonstrate improved learning of novel tasks (Rooney & Cowan, 2011; Ziv, 2017). These methods are also associated with stronger human-dog relationships and more secure attachment styles, indicating better emotional wellbeing (De Castro et al., 2021; Johnson & Wynne, 2024). Reward-based training may additionally act as a form of enrichment by encouraging cognitive engagement and positive emotional states (Todd, 2018).

For pet dogs, this means training that supports learning and emotional safety.

Aversive Training Methods: What the Evidence Shows

Aversive training methods rely on positive punishment and negative reinforcement, using unpleasant stimuli to suppress unwanted behaviour. Common tools include choke chains, prong collars, and electronic shock collars (e-collars). The goal is typically to reduce the frequency of a behaviour, often as quickly as possible.

Some studies report that aversive methods can rapidly suppress specific behaviours under tightly controlled conditions. For example, Johnson and Wynne (2024) found that e-collars inhibited chasing behaviour quickly when applied by highly skilled professionals following strict protocols. These findings are sometimes used to justify aversive tools in situations perceived as high risk.

However, behavioural suppression does not necessarily equate to learning a safe, alternative behaviour. Research consistently associates aversive methods with increased stress, fear, and anxiety. Dogs trained using aversive tools show more stress-related behaviours, avoidance responses, and signs of negative emotional states, even outside of training contexts (Rooney & Cowan, 2011; Ziv, 2017; Johnson & Wynne, 2024).

Physiological stress responses, including elevated cortisol levels, have also been documented, particularly when dogs fail to comply during high-arousal situations (Ziv, 2017). Dogs exposed to frequent punishment are more likely to display aggression, fearfulness, and pessimistic cognitive bias, suggesting compromised emotional welfare (Brand et al., 2024).

Effectiveness Versus Welfare

When training methods are compared, the research does not support the claim that aversive methods are more effective overall. Surveys consistently show higher obedience scores in dogs trained primarily using rewards, with obedience correlating positively with the number of behaviours taught through reinforcement rather than punishment (Hiby et al., 2004; Rooney & Cowan, 2011).

Reward-based methods are also effective for long-term behaviour change. While instinctive behaviours such as chasing can be challenging, this reflects the nature of the behaviour rather than a failure of reinforcement. Chasing is intrinsically rewarding for many dogs - the act of chasing itself releases reinforcing neurochemicals and strengthens the behaviour. Successfully interrupting such behaviours requires teaching a well-reinforced, incompatible alternative behaviour over time, not merely suppressing the behaviour in the moment.

A Case Study: Critiquing the Johnson & Wynne Study

Johnson and Wynne’s (2024) study has been cited as evidence supporting the use of shock collars for chase inhibition. However, Bastos et al. (2024) provided a detailed critique, highlighting significant methodological and welfare limitations.

Training Protocol Concerns

Bastos et al. argued that the reinforcement-based groups were not trained using appropriate operant recall protocols. Instead, a classically conditioned word (“banana”) was paired with food, which is insufficient to interrupt a highly motivated predatory sequence (the chasing). No incompatible alternative behaviour, such as returning to the handler, was trained, making the comparison between aversive and reinforcement-based methods inequitable.

Additionally, all dogs were allowed extensive opportunities to chase the lure before and during training. Since chasing is inherently reinforcing, this design likely strengthened the behaviour the reinforcement protocol was attempting to inhibit, setting it up to fail.

Welfare Assessment Limitations

Bastos et al. also challenged the conclusion that shock collars imposed minimal welfare costs. Johnson and Wynne did not define distress operationally, failed to code common behavioural stress indicators (e.g. lip-licking, pinned ears, tail position), and lacked sufficient long-term cortisol data. Importantly, dogs continued to receive shocks across sessions, indicating ongoing reliance on punishment rather than completed learning.

Bastos et al. concluded that future research should compare aversive tools with well-designed, non-aversive operant protocols, particularly given the existing body of evidence linking aversive methods to negative welfare outcomes.

Regulation, Welfare, and Ethical Practice in the UK

The dog training industry in the UK is largely unregulated, meaning anyone can call themselves a dog trainer or behaviourist. This makes it difficult for owners to distinguish evidence-based practice from misinformation, particularly on social media.

Professional bodies affiliated with the Animal Behaviour and Training Council (ABTC) and organisations such as the CCAB Certification promote welfare-focused, evidence-based practice and overwhelmingly discourage the use of aversive methods. In Wales, the use of electronic shock collars is illegal. The Animal Welfare Act (2006) places a legal duty of care on owners to protect animals from unnecessary pain and suffering, which directly informs acceptable training practices.

Veterinary organisations including the British Veterinary Association (BVA) and the British Small Animal Veterinary Association (BSAVA) recommend against aversive tools due to their risks to physical and emotional welfare.

When choosing a trainer, it is important to consider not only effectiveness, which may be exaggerated in short social media videos. But also, welfare, ethics, and professional standards. Trainers aligned with ABTC guidance prioritise humane, evidence-based methods.

What This Means for Dog Owners

Quick “fixes” often rely on suppression, not learning.

Instinctive behaviours take time to change safely.

Welfare and emotional safety matter just as much as obedience.

If a method causes fear or pain, there is usually a better alternative.

Conclusion

Scientific evidence shows that while aversive methods can suppress behaviour in specific circumstances, they carry significant and well-documented welfare risks. Reward-based methods are associated with positive emotional states, stronger human-dog relationships, and comparable or superior long-term effectiveness. Leading professional bodies within the UK consistently discourage the use of aversive training methods, shaping current best-practice standards for dog trainers and behaviour professionals.

When both approaches can achieve behavioural change, but one relies on fear or pain while the other does not, the decision becomes an ethical one. Prioritising welfare should always be at the heart of dog training.

Further reading / references:

Animal Welfare Act 2006, c. 45. (2006). UK Legislation. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/45/section/9

Bastos, A. P. M., Warren, E., & Krupenye, C. (2024). What evidence can validate a dog training method? Learning & Behavior, 53(3), 227–228. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13420-024-00658-9

Brand, C. L., O’Neill, D. G., Belshaw, Z., Dale, F. C., Merritt, B. L., Clover, K. N., Tay, M. M., Pegram, C. L., & Packer, R. M. A. (2024). Impacts of Puppy Early Life Experiences, Puppy-Purchasing Practices, and Owner Characteristics on Owner-Reported Problem Behaviours in a UK Pandemic Puppies Cohort at 21 Months of Age. Animals, 14(2), 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14020336

De Castro, A. C. V., Araújo, Â., Fonseca, A., & Olsson, I. a. S. (2021). Improving dog training methods: Efficacy and efficiency of reward and mixed training methods. PLoS ONE, 16(2), e0247321. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247321

Hiby, E., Rooney, N., & Bradshaw, J. (2004). Dog training methods: their use, effectiveness and interaction with behaviour and welfare. Animal Welfare, 13(1), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0962728600026683

Johnson, A. C., & Wynne, C. D. L. (2024). Comparison of the efficacy and welfare of different training methods in stopping chasing behavior in dogs. Animals, 14(18), 2632. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14182632

Rooney, N. J., & Cowan, S. (2011). Training methods and owner–dog interactions: Links with dog behaviour and learning ability. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 132(3–4), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2011.03.007

Todd, Z. (2018). Barriers to the adoption of humane dog training methods. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 25, 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2018.03.004

Ziv, G. (2017). The effects of using aversive training methods in dogs—A review. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 19, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2017.02.004